Simply put, children don’t do everything we ask them to do when we ask them to do it. We often assume it’s because they didn’t understand what we said so we repeat ourselves, sometimes in a louder voice. If that doesn’t work, our own frustration grows which inhibits our ability to remain emotionally regulated and problem-solve what to do next.

But, in many situations, we’ve already missed a step. Somewhere between repeating ourselves and assuming kids are just giving us a hard time, we often overlook the possibility that a child isn’t capable of doing what we’ve asked (yes, even if they were able to do it yesterday or when they were rested or when they had our undivided attention).

Skills can vary depending on circumstances including but not limited to our mood, confidence, motivation, physical comfort, or fatigue. This is true for all of us, not just kids.

So, what does this look like in a classroom?

When Kindergarten students begin school, no one expects them to know what to do. Teachers spend time building trust and safety, a sense of classroom community and routine, and then the learning begins.

For neurodivergent students, many continue to lack skills needed to be a student later into elementary school so it’s hard to remember that we may still need to support their executive functioning skills, social skills, and emotional regulation skills before asking them to engage in academic learning.

In order to complete a task that a teacher has asked a student to complete, that student must not only understand what is expected of them, but also needs to feel emotionally safe to begin a task they are unsure about (Remember: learning is a vulnerable experience) PLUS they must have the skills to do the thing being asked of them.

When students don’t respond in an expected way, teacher and school administrators may think:

“He is choosing to put his head down and not to get started.”

“She is choosing to argue with me instead of getting to work.”

“He is choosing to engage in unsafe behaviors.”

When I hear these phrases from educators, it’s time to get curious and start problem-solving. If a student with ADHD isn’t getting started when asked, it’s likely due to a lagging executive functioning skill. If an autistic student avoids a task or activity, more times than not it is due to a stress response and not a choice.

Neurodivergent students experience more lagging skills and are triggered more often and more easily than their neurotypical peers.

In some cases this is due to a sensitive nervous system and sometimes it’s due to previous school experiences. Many times it’s due to both. Remember, getting started on a task requires feeling safe in the environment, feeling connected to the person asking you to do the thing, plus the skills AND motivation to carry out the task. If one of these things is missing, a student’s ability to begin the task will likely crumble.

Below, I walk you through how to identify a student’s stress response and how to respond in these moments. I want you to feel prepared and confident when supporting students in these stressful situations.

Parents, you can gift your child’s teacher a subscription to my Substack by clicking below!

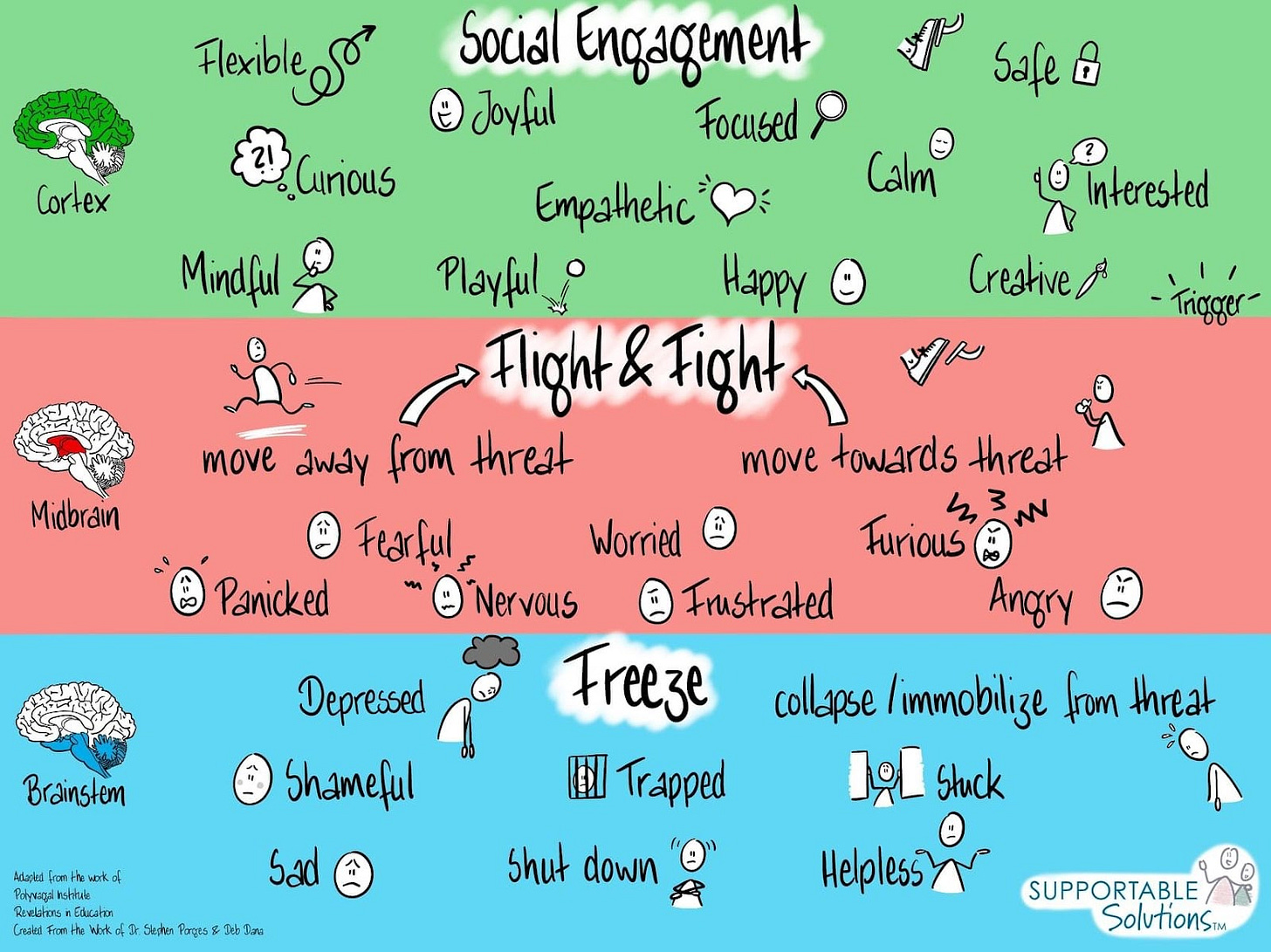

This crumbling will have different levels of severity depending on how the child responds to stress. I love this visual from Supportable Solutions™ which shows the three states of our nervous system depending on the perception of threat around us.

When we feel safe and connected to either our people or our interests, we are able to learn. When we perceive a threat, some of us go into fight or flight and some go into freeze. This is a naturally-occurring, automatic response our brain has to defend us from danger. For many neurodivergent kids and adults, their nervous systems are more sensitive to these perceptions and many register a danger response that a neurotypical brain would not. Therefore, it’s important to believe a child when they communicate overwhelm, even if it doesn’t quite make sense to us.

These defensive responses are also not a choice. That would be like saying that I chose to run from the grizzly bear I saw in the woods or that I chose to grab my child’s arm when they stepped into the street in front of an oncoming truck. Choosing these responses would imply that I had the time to consider an alternative option and decided that this action was best.

When we react to perceived danger, there is no time for a choice. Our brain immediately responds in the best way it knows how to feel safe.

Now, of course a child cannot be harmed by a math worksheet in the same way they would be by oncoming traffic, but it’s their perception of difficulty that is the “danger” here. If the task is too overwhelming due to high expectations and lack of skills, you may get a “non-compliant” response of freezing with a student’s head down on their desk. This is what the child knows how to do under these circumstances.

So, we need to get curious and figure out the following: Is the expectation too high? What skill is missing? And, how can I connect with this student to help them feel safe in this moment of learning? In other words, we can teach the child a safe, more productive way to respond when met with a challenge.

Imagine instead saying,

“He’s not getting started on his own. I wonder what feels overwhelming to him about this assignment?”

“She is getting upset and asking lots of questions about this assignment. I wonder what and how I could clarify this for her?”

“He is running and hiding under a table every time he’s asked to write. I wonder if he needs support with coming up with ideas, organizing his thoughts, fine motor skills, or all of the above?”

Problem-solving in these moments will take more energy and practice from the adult in the room, but it will be worth it. That’s why I don’t teach these ideas without also discussing self-care for educators as well as parent-teacher collaboration. We have to keep showing up for our kids so they will learn to keep showing up for themselves when making mistakes during the learning process.

Let’s Stay Connected!

~Dr. Emily

If you’re interested in Dr. Emily’s on-demand professional development for educators or having her speak at your school, just click below!

I’m Dr. Emily, child psychologist and former school psychologist, and I’m on a mission to help parents and teachers be the best adults we can be for the neurodivergent kids and teens in our lives. This isn’t about changing the kids, it’s about changing us. Learn more with my resources for parents, teachers, and schools at www.learnwithdremily.com.

**All content provided is protected under applicable copyright, patent, trademark, and other proprietary rights. All content is provided for informational and education purposes only. No content is intended to be a substitute for professional medical or psychological diagnosis, advice or treatment. Information provided does not create an agreement for service between Dr. Emily W. King and the recipient. Consult your physician regarding the applicability of any opinions or recommendations with respect to you or your child's symptoms or medical condition. Children or adults who show signs of dangerous behavior toward themselves and/or others, should be placed immediately under the care of a qualified professional.**

I was struck by the correlation of children's resistance to learning as a survival defense mechanism. Those questions you positioned are helpful: is the expectation too high? how may they see this as a threat?, etc. I agree that teachers can be overly simplistic in assuming the worst about a student. Similar to neurodivergent being a factor, trauma plays into this and effects prefrontal cortex functionality, which I see play out in my adult clients.

I do wonder how tailored you can make a student's learning plan (IEP) in light of teaching 20-30 kids who are all at varying degrees of function and capability? I think about this a lot in that students shouldn't be categorized by age as much as functionality. Maybe I'm naive but I wonder how that structure would go instead of forcing kids into this generalized category based on age alone.